A Brussels exercise network

Three weeks ago we posted an article about the research part of our study “How to design the runner-friendly city of Brussels?”. The runners appeared to have twofold desires. On the one hand, numerous small (running) friendly adjustments to surfaces or lighting, or additions of water taps or signage are of great value. But the runners also argued for a structural change in the layout of the city; less nuisance from (dangerous) intersections, less shared space with motorized traffic, less particulate matter and more greenery in Brussels city streets.

This article summarizes a number of spatial principles that we consider to be decisive in the search for more movement-friendly networks for and throughout the city. The basis for these proposals was created on the one hand by the wishes of runners from the 'running survey'. In addition, data from more than 100,000 running activities was mapped, collected from activity trackers. In this, runners speak with their feet about the Brussels city routes.

In its 'good move' campaign, Brussels (like many cities) is looking for a new balance in the public space between motorized traffic, healthy-moving people, quality of stay, greenery and a diversity of other functions.

During the lock-down period, the space for cyclists and pedestrians has been increased in various streets. Several new cycle paths were created, as well as various so-called 'living streets' or 'playing streets'. If we visualize the bicycle developments throughout the city, however, it also becomes clear that both the new bicycle space and the existing separate bicycle paths are mainly clustered on the major motorways.

These can be excellent bicycle routes for fast, through bicycle traffic. They are clear structures with a traceable orientation. However, they are also mainly investments in traffic/transport, less in the quality of an area. For example, the runner does ask for safe bicycle space, but not only next to the largest, polluting highways. And many cyclists share this view.

The new car-free 'living streets/playing streets' in the neighborhoods are a step in that direction, but for the time being no connected network across the entire city is intended. There is also already an ambition for a 'continuous distance' in Brussels; a network of green streets between the city parks and the surrounding landscape. However, if we project running use on these intended routes, it becomes apparent that many routes are currently underused.

That's because the intended green connections usually don't follow people's intuitive movement lines. As walking and cycling routes, they do not have a clear direction. Where they do have this, they are intensively walked on. They lack what the bicycle routes along motorways do have: a logically traceable orientation. The runner actually argues for an intermediate variant that combines the best of both worlds. A green city network, precisely on the strongest lines of movement of people, but separate from the major highways.

hierarchy of streets

One runner put it this way:

The existence of a system of major highways is actually not the core of the problem. To a certain extent this is also part of a city, they are often located in the larger streets between the city districts. The great lack is that there is no quiet counterpart in the neighborhoods. From continuously connected streets in which moving people are the primary users, in an environment with a high quality of stay, greenery and a diversity of urban functions that benefit from a pleasant living environment.

Although Brussels streets are enormously hierarchical in their widths, degree of continuity, planting and building functions, this hierarchy is lacking in the layout of the street surface. The car takes up most of the space in almost every street, and central neighborhood streets are also occupied by over-dimensioned highways and parking spaces. And it is precisely in those central neighborhood streets that playing, cycling, walking, sitting, meeting (potentially) is the best.

Green connected ambitions

The runner also points out one of the most important characteristics for the 'quiet neighborhood streets': they must be continuously connected to the parks, waterways and the landscape. It turned out to be typical for Brussels that in the running survey the runner asked more often for more pleasant and greener connections between existing green spaces, than for more greenery in an absolute sense.

Again an idea initiated by the runner, but we see a much greater potential in this. It ensures that the most pleasant places in the city form a coherent system. It is a system for moving people, both recreational and utilitarian. With more greenery and less pavement, it is simultaneously an ecological city network, a system for aboveground flow and collection of water, and also cooling the city. It offers the opportunity to link playgrounds in the neighborhood with safe routes, and neighborhood centers with parks and flower beds. A system of the healthy city; an urban fabric that forms the pleasant counterpart to the large traffic structure. It is a physically connected network, but above all it connects healthy ambitions.

How can this be given shape in different city districts?

Although the ambition concerns a cohesive network, the specific elaboration of this is different in each city district. Because in different city districts, the characteristics of streets are different, but also because the green structures in each district differ. On the basis of which characteristics can the most promising streets and structures be identified? We conducted research in four Brussels city districts. We show three here (Anderlecht, Jetten, Central)

Anderlecht; the park system (more)

Of all the Brussels districts, Anderlecht is actually the district where a 'park system' is already the most present. In principle, Anderlecht's parks are conceived as a connected, cohesive system that connects greenery and various districts. Viewed from above, the green parks branch off into various green linear structures, which also touch on the outer urban landscape. The runner is an interesting target group to make statements about the extent to which this is also used and experienced as a connected system.

The use of space by runners shows that a number of parts of the park system are used to a limited extent. It is especially the round of Pedepark that is walked a lot, while this is actually quite far from the residential areas. But it is a simple and trackable walk.

And that shows the problem of the Anderlecht 'park system': it seems to have a certain degree of unity from above, but at eye level the walking and cycling route are incomplete, often broken, difficult to follow, without hierarchy, and of poor quality.

At various places in the Anderlecht park system, proposals have been made to increase the continuity of the greenery, together with pedestrian and bicycle paths. This system would then come into its own even more if a number of streets in the city districts were given more bicycle and foot space, connecting to the various centers of Anderlecht. They do not even have to have a green character, but they should preferably be in line with the park system. The park system, together with those urban routes, then forms the healthy counterpart on the major arterial roads. Connections with improved routes along the Canal complete the system and ensure connections with the surrounding city districts.

jette. Park ing

In Jette too, the opportunities for expanding green, healthy exercise streets lie in the typical features of the green urban structure. Around the Elisabeth Park is a system of streets that were once designed in conjunction with the Elisabeth Park. It is no coincidence that these are spacious streets of 28-30 meters wide, with beautiful large, old tree-lined structures. They sometimes extend far into Jette, in the direction of other surrounding parks and district centers. These kinds of unique ingredients can form the basis of movement-friendly transformations. However, those spacious, 'green' streets around Elisabeth Park mainly consist of one function: parking. Almost all streets contain four rows of parking lanes, nicely between and under the trees.

Those are actually the best streets; you can solve a problem twice. Firstly, by (partly) removing parking space, space is created, beautifully spacious under the trees in the neighborhood streets. Secondly, offering so much (cheap) space for parking at the front door is the primary breeding ground for high car ownership, resulting in a high share of car use and therefore high traffic intensity. The potential for reducing traffic congestion lies much more in the reduction and relocation of parking spaces than in the removal of carriageways. And if we can reduce car use with this, even more safe space will be created for cycling and walking. Then we end up in a movement-friendly vicious circle.

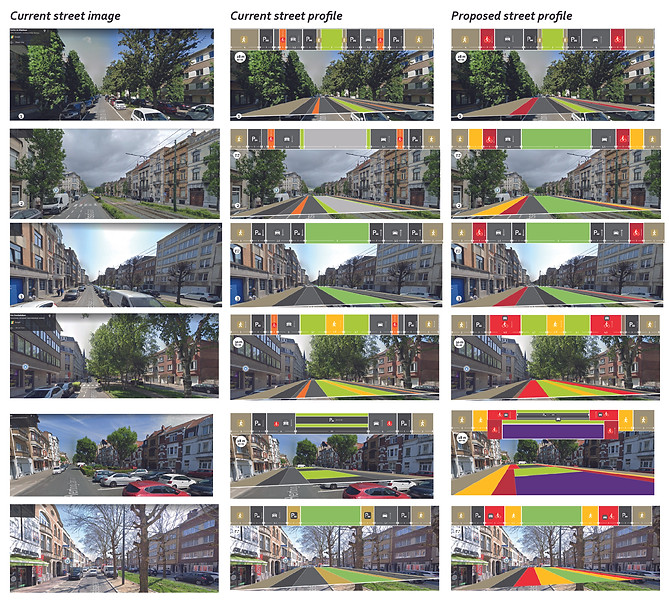

In the Jettense neighborhoods next to the Elisabeth Park, we made proposals for all kinds of streets, how a parking space reduction can ensure much greener, more exercise-friendly street profiles. What exactly is desirable in which street is highly dependent on a number of properties. Are there valuable avenues of trees, and how are they placed (yes, we'll start with greenery)? How much space do they leave on which sides? To what extent is the road important for through car traffic (hierarchy!)? In case of through car traffic, a separate bicycle path is desirable. Can it also become a destination traffic road? Then car and bicycle can share the space and there is even more room for plants, footpaths or other functions. The changes can also be presented step-by-step; which profile change constitutes a first step? And what is the ultimate street profile?

An important starting point for changing street profiles is the degree of continuity in which you implement them. When attractive, movement-friendly profiles are implemented consistently between two destinations (for example, parks, or other attractive urban places), a route becomes a connection, and also a more valuable investment in an area. In Jette, for example, the Overbekelaan is already attractively profiled in the southern half, but unfortunately this profile was not continued in the northern half, which ends at Park Ganshoren. Park Ganshoren is lost, also because of this. The paths and entrances to the park are invisible and do not connect to anything. It is an unsafe and poorly usable park. So extend the attractive profile of the van Overbekelaan and use this to invest directly in the routes and entrances of Park Ganshoren. There is also such an opportunity between the Tours&Taxis park. In connection with T&T Park, a new fast cycle route can create a new, green, lively front for the streets adjacent to the railway. Investments in routes, for example, are not just investments in transport, they are mainly investments in the quality and quality of life of the city.

Central; connect the green dots

In the most urban part of Brussels, the urgency for increasing mobility space and human streets turned out to be the highest: the density of the motorized infrastructure is also greatest here. Because the urban structures are busy and grand in all directions, this is where the city is the most complex for healthy moving people. In addition, there are widespread, many green 'dots' of limited size that are not easy to combine in a loop.

But here too the urban landscape has an important characteristic that can form the logical guideline for a connecting green movement structure. From the elevation map of Brussels it can be seen that in a north-south direction, several (ponds of) parks are clustered along a continuous urban valley. This is the course of the former Maelbeek. The nice consequence of this is that this low section (although the stream no longer exists) runs freely under the intersecting heavy infrastructure in a number of crucial places and the height differences over this section are minimal. Moreover, the route is not really crucial anywhere as a through car traffic route.

Despite this, almost the entire line is incorrectly set up. The 'Graystraat' is currently better called 'Greystraat'. Furnishing such a low-lying street so petrified is also asking for water problems.

And that makes it strong to focus here on making one very long, uncompromisingly continuously connected, green, car-free, limited paved line. A 'natural' backbone that links all the small parks and flower beds together. By softening the route, water can be drained off naturally again via the lowest part of the city. The Maelbeek is being revived.

It is also an ongoing natural reference structure, which re-orders your mental map of the city. Various other routes with good pedestrian and bicycle routes link up logically on this line, such as the route of the stone road and the new viaduct park along the railway.

It's going to be so hard

The runner is certainly not the most important user of the city. However, the runner's glasses provide perhaps the most fun and logical perspective to think about how we can transform into a healthy, green, exercise-friendly city. He gives every reason to reason transformations of urban fabrics from the natural nature, qualities and hierarchies of city streets. He always binds the interests of the pedestrian and the cyclist, on whose paths he walks. The location, structure and importance of greenery suddenly become an obvious part of 'traffic science'.

On the basis of comparable starting points, a network of green, exercise-friendly routes has been proposed at the scale of the entire city. It is a mix of existing through bicycle structures and residential streets, with newly proposed green connections between the green spaces of the city and the Brussels canal. On top of this there are many extra options for all kinds of walking-friendly adjustments and additions. Together they make that ideal (running) map of Brussels. That is certainly ambitious, but we can see it going so quickly!